Xavier Johnson and the fire from within

You could see it. Palms up, then fists clenched into a ball, placing them on his temple, covering his face in frustration. He walked to the bench with three fouls at the beginning of the second half against Wisconsin as he took a barrage of words from head coach Mike Woodson.

Xavier Johnson had just played arguably the most efficient half of his career at Indiana with seven points, five rebounds and six assists. Indiana led by as many as 22 points. But toward the end of the first half, things started to unravel. After a first-half foul, Xavier held up his arms and looked at the referee in disbelief. Indiana’s lead eventually evaporated. With two minutes left and Indiana up by just two, Xavier had the ball tipped from behind and took a spill, his arms outstretched on the hardwood. He looked up for a foul. Nothing was called.

In the end, the Hoosiers lost their 19th consecutive game in Madison. Xavier shot 1-of-10 in the second half.

There are times when watching Xavier play is like riding a rollercoaster. Washington head coach Mike Hopkins once described him as “a Ferrari without brakes.” It sometimes produces moments of jaw-dropping elusiveness and athleticism. It sometimes also produces fouls and turnovers.

But in many ways, Indiana’s potential this season is in the hands of Xavier’s fiery passion. After three years at Pittsburgh, he’s averaging 10.3 points, 3.7 rebounds and 4.2 assists per game this season as the starting point guard for Indiana. Between those numbers, he walks a tightrope between intensity and serenity.

In the moments following the game against Wisconsin, though, Xavier becomes a caricature. A static figure, one that is an easy target for onlookers to blame. One whose identity is defined by a hand gesture or facial expression.

In reality, life isn’t one-dimensional. There is depth. How Xavier became this ultra-competitive, ambitious and relentless player can’t be explained by a two-second play.

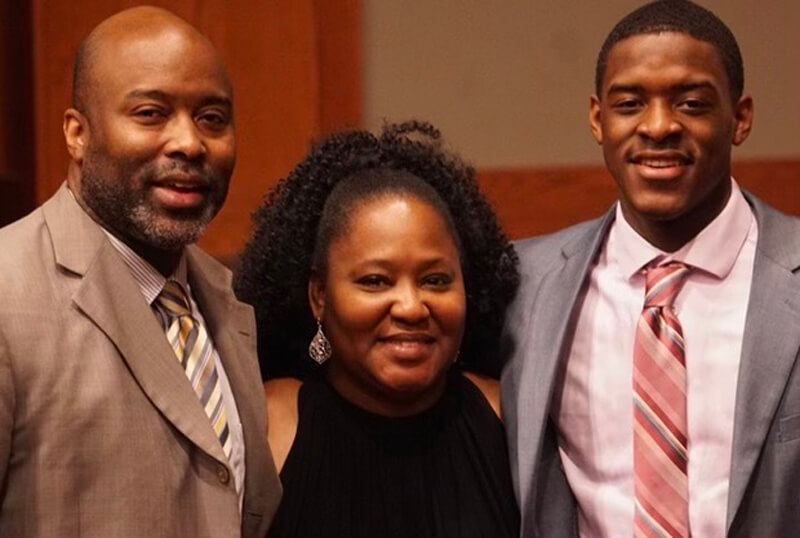

To understand who Xavier is — and the man he’s trying to become — you have to start with his parents, La’Kesha and Michael Johnson. They are both Air Force Veterans with a combined 44 years of service. While working in the Air Force, Michael made time to start a youth basketball program in Virginia. La’Kesha used to drive about four hours roundtrip, dropping Xavier at Bishop O’Connell High School in Arlington, Virginia, on her way to and from work so her son could pursue a future in basketball.

“I can’t,” Xavier says, “Ask for any better parents.”

Xavier carries a heavy burden to win, not only for himself and his teammates but to repay the sacrifices of his parents.

It’s fueled by a fire that was here long before he was even born.

***

Years ago, when Michael had just finished his collegiate basketball career at Division III Covenant College, he was living at home and figuring out what was next. His parents, though, wanted to make sure that he wasn’t becoming complacent.

Michael’s father worked as a teacher, principal and pastor at Chamblee High School in Georgia, a little more than 20 miles from their home. In the mornings, Michael would ride with his father to the school. When they arrived and his father started working, Michael would have the rest of the day to find his way back home. He went on backstreets, running some of the way, walking other parts. He was given a few dollars, which he’d use to to get breakfast and also go to McDonald’s to get two cheeseburgers for lunch. Normally, he’d stop at a gym for a couple of hours to play basketball before continuing his trek. His goal, he said, was to be home by 10 or 11 p.m.

“It wasn’t because they (my parents) didn’t love me,” Michael said. “They were just trying to… challenge me.”

After briefly playing on the semi-professional basketball circuit, Michael decided to join the Air Force. That’s where he met La’Kesha in 1996 at MacDill Air Force Base in Tampa, Florida. They married a year later. Soon after, they had their first child, Chaleb. Xavier came next. They did everything to not only provide for their children, but eventually give them opportunities to attend prep schools and go to basketball camps. Michael picked up extra jobs while still on active duty. He’d wake up around 3-4 a.m. to deliver newspapers, then sleep in the parking lot of the Air Force Base before starting work at 7:30 a.m. Other times, he worked as a security guard at a hotel and refereed local basketball games.

When Xavier was still a toddler, Michael went overseas. He was deployed to Iraq as a medic from 2004-2005 as part of Operation Enduring Freedom. Some mornings, he remembers, he’d wake up to the sounds of bombs detonating and sirens wailing. Michael worked in the emergency room, which was just a tent surrounded by barricades to protect it from mortar shots. Buses and planes went flying by. One time, Michael had to perform CPR on a sniper who had been shot in the head. During those months in Iraq, Michael created a purpose-driven life ministry to help spread positivity.

“Giving my life for others,” Michael said. “You didn’t know if you were going to make it out of there.”

La’Kesha spent 24 years in the Air Force as a training manager, with stints in Italy and Korea before meeting Michael. While Michael was away, La’Kesha took care of the two kids, while also working a full-time job at the base. During her service, she earned several awards — including Military Member of the Month and Training Manager of the Year, among others.

Even after retiring from the military, La’Kesha has displayed the same relentlessness in her civilian life. She recently earned her Master’s in Business Administration from Strayer University, graduating with a 4.0 GPA in what has been an adverse year. She was in the hospital for more than a week with COVID-19 but still completed her schoolwork during that time. She dealt with the death of her brother. She has been flying back and forth from Virginia to Georgia to take care of her father. She’s also continued to help raise her two youngest children, Xavier’s siblings, Lathan and Mya.

“Everything that we do, our kids are watching,” La’Kesha said. “…I just pressed on. I just had to do it for my family.”

Michael and La’Kesha are also extremely competitive. La’Kesha, who ran track when she was younger, looks to her left and right during group sessions at Orangetheory Fitness to try to outdo her peers’ workouts. During heated game nights, La’Kesha has the upper hand in Scrabble. “She’s like a walking dictionary,” Michael said.

Similarly, Michael says he once broke both his wrists in a basketball game, but refused to come out. He compensated by hoisting shots with both hands and ultimately scoring more than 30 points. If he lost video games to his friends, he said he studied the game or bought books to improve his skills and beat them. During quarantine, the family played flag football and Michael was so dedicated that he started drawing up plays.

“Like it was the Super Bowl,” La’Kesha said.

***

The buzzer had just sounded and the players on Team Takeover were celebrating, peeling off their jerseys for the summer after winning a 17U tournament in Las Vegas. It was 2017 and the team was filled with future Division I prospects — Jeremy Roach (Duke), Hunter Dickinson (Michigan), Justin Moore (Villanova), Myles Dread (Penn State) — all of whom played in the Washington Catholic Athletic Conference in the DMV, one of the most competitive leagues in the country. But as the team was euphoric, Xavier had something to say.

“I’m going to be the player of the year in the WCAC,” Xavier declared.

Some of his teammates were taken aback. Others laughed. “Everybody was like ‘X is adrenaline drunk,’” Team Takeover coach Doug Martin said. But Xavier said it with a straight face.

The next season?

Xavier won the WCAC player of the year. He averaged 18.4 points per game, leading an overlooked Bishop O’Connell team to the finals of the Virginia Independent Schools State tournament. Each game, Xavier lined up against his summer teammates with “almost a look of disdain,” Martin said.

“If you tell the kid he can’t do something, he’s twice as likely to do it,” Bishop O’Connell head coach Joe Wootten said. “He’s a great competitor, he loves to prove (people) wrong.”

Getting to that point was a process for Xavier.

Michael and La’Kesha instilled in their kids the discipline they learned in the military. Xavier always had to complete chores: taking out the trash, washing dishes, sweeping the floor. When it came to basketball, Michael was hard on Xavier in the same way his parents were on him. Xavier sometimes wouldn’t ride home with his father because he critiqued his game with such depth. At one point, Michael became fed up with the fact that his son never went into an all-out sprint. One day, after a workout in grade school, he made Xavier run four to five miles back home in the dark. Xavier was moping and crying as Michael trailed behind in the car.

“It’s funny to me today,” Xavier says. “But he actually made me walk home. It was far, too.”

As a freshman in high school, he played junior varsity and was just 5-foot-6 and 130 pounds. Before his sophomore year, Wootten told him he likely wouldn’t make varsity. The family talked about transferring, but Xavier said no. He wanted to prove himself at O’Connell. That summer, Xavier and Michael worked out three times a day, five days a week. They got up at 7 a.m. and hit the gym for a couple of hours. Then had a meal. Then worked out for a couple more hours. Then had another meal. Then went back for a third workout at night.

Xavier made varsity his sophomore year and ended up starting by the end of the season. That summer, he started playing for 16U Team Takeover and his passion became evident to those in the program. He’d arrive to practice an hour early to get up shots. If he didn’t do a drill correctly, Martin would see tears well up in Xavier’s eyes in frustration. One time, Michael says, Xavier broke his finger and was supposed to be out for 4-to-6 weeks. Instead, Xavier was back playing in one week.

He darted up and down the court in a blur, but sometimes tried to do too much and turned the ball over. “He wants the game to be perfect,” Martin said. It resulted in Xavier sitting the bench at first on Team Takeover. Martin tried to help Xavier work through it, and by the end of the first summer, Xavier was the trusted closer of the games. When Martin would tell him to finish off the contest, Xavier would look Martin in the face and say “I got you.” And Xavier would follow through.

“It was so military-like for him,” Martin said. “It was like ‘I did my job.’ It wasn’t the pageantry of anything. It was just like ‘I did what I was supposed to do.’”

After continuing to work through turnover troubles as a junior, it eventually gave way to his dominant senior season at O’Connell. He took charges and dove on the floor. He originally committed to Nebraska, where he had a relationship with now-Indiana assistant coach Kenya Hunter. But Hunter left. Xavier decided on Pittsburgh instead.

There’s also a side of Xavier again reflective of his parents, but one that is often overshadowed by his tenacity on the court. Talk with Xavier and he is soft-spoken. One time during AAU, he told his coach that he didn’t want to start because it’d give the team a better chance to win. He has given his time to speak to younger kids at Team Takeover, telling them what it takes to get to the next level. Growing up, he would volunteer at the homeless shelter with his family. With his high school team, he helped work at a basketball club for kids in special education. At Pittsburgh, Wootten said, when one of them went to watch Xavier play, he came out of the locker room to smile and visit.

“(He) treats everyone with respect, treats everyone as if (he’s) their friend,” Wootten said. “Just a really good person off the court.”

***

In the days following the Wisconsin game, Xavier watched film. His coaches pointed out his change in body language during the second half.

In a meeting this summer, IU assistant coach Dane Fife told Xavier that unlocking his full potential was not a matter of his physical abilities. It was a matter of harnessing the mental side.

As a freshman at Pitt, he was named to the ACC All-freshman team. Last season, before leaving Pitt in February, he averaged 14.2 points and 5.7 assists per game. But there were moments where Xavier’s intensity worked to his detriment, like the stretch where he had three technicals in five games. Over the summer, after deciding to transfer to Indiana, he was asked what he’d tell the freshman version of himself.

“Honestly, just to just keep my head on and not let the refs take me out of the game,” Xavier said.

Growth takes time. Coaches have been watching film with him, showing him tangible evidence of where he lets things get to him. Fife tells him to focus on encouraging his teammates rather than letting external factors bother him. “Just hoop,” his coaches tell him. Earlier this season, Xavier said, he was frustrated with a call, but simply passed the ball back to the referee.

“I find myself getting better every day,” Xavier said, reflecting on being away from home during his transition to IU. “Finding more about myself.”

More than anything, he wants to win. He didn’t win much at Pitt. It bothers him now.

This, of course, is part of who he is. Which brings us back to where his will to win came from. On a recent night, he doesn’t take long to think about the answer.

“My parents,” he says.

“My mom just got a degree. That’s like her winning in life. My dad, he strives to be great in everything that he does because he wants to be a better man every day and provide. He wants us to be a better man than him.”

Xavier wants to succeed for his mother, ensuring she can live a comfortable life. Xavier wants to thrive for his father, fulfilling his hoop dream. Xavier wants to win for his uncle, with whom he was building a bond before his recent death. Xavier wants to set an example for his little brother Lathan, who, he believes, will be a better basketball player than himself.

Xavier says his passion gets the best of him when he commits a turnover and tries to make up for it. But when that happens, it’s almost as if he’s not only chasing an opponent, but also something larger.

Xavier is a son, a nephew, and a brother, just trying to make his family proud.

Category: Media

Filed to: Xavier Johnson